Blog

Early stakeholder engagement in workplace projects: a toolkit approach to inclusive design

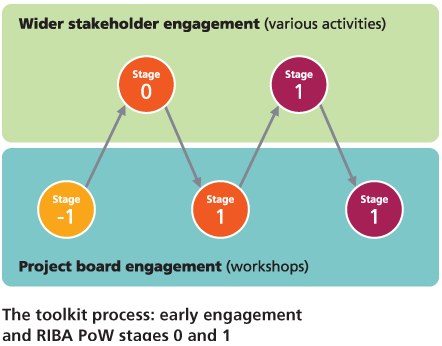

Successful workplace change initiatives rarely begin with conversations about the workspace; engaging stakeholders early-on regarding their needs is far more likely to produce positive outcomes.

James Pinder, Ian Ellison & Sinead O’Toole

ENGAGEMENT • WORKPLACE CHANGE • LEADERSHIP

Early stakeholder engagement in workplace projects: a toolkit approach to inclusive design

You have probably heard the now-famous claim, originating from a number of mutually-reinforcing Harvard Business Review articles in the 1990s, that “70% of all organizational change initiatives fail”. The claim has actually been shown to be unfoundedii. However, whilst the rate of failure in projects might have been exaggerated, what we do know is that many projects don’t go as well as they could or should.

Over the years scholars and practitioners have spent a significant amount of time trying to understand why projects fail or under-deliver. Although every project is different, time after time recurring issues have been found to negatively impact on project performance across a range of sectors. In a 2015 paper on why projects failiii, three eminent academics at Cranfield School of Management summarised these issues under four main headings:

Unclear objectives, definition or scope;

Inappropriate/inadequate project teams and leadership;

Poor project planning and controls; and

A lack of stakeholder communication and consultation.

If you’ve been involved in a workplace project – by which we mean a project that involves changing someone’s working environment – you’ll probably recognise some or all of these issues. Perhaps you fell afoul of them, or perhaps you dealt with them successfully. It’s also not difficult to see how these issues can affect one another. For instance, if you don’t have the right project team in place, how likely is it that the project will be scoped, planned, or managed effectively?

Acknowledging these interrelationships, our primary focus in this article is on the first and fourth points listed above. From our experience these factors are where workplace projects tend to go wrong, because everyone’s effort is focused on delivering the project, rather than understanding its purpose and impact.

For reasons we’ll explain below, client organisations can find these issues particularly challenging. The end result is that even if a project is competently managed – with respect to time, cost, and quality – organisations still regularly end up with the wrong workplace solutions for their specific needs and/or a lack of buy-in from their employees.

Beyond imagined user needs

For many organisations, workplace projects have traditionally been more about workspace – about building fabric, architecture, interior design, décor and/or furniture – and less about the people working in them. Think about this the next time you see those glossy promotional images of newly completed workspaces without any people in them. An industry has grown up to help clients deliver new workspaces. However, what is – on the face of it – a positive development has created its own problems.

One such problem is that discussions about new workplaces tend to be dominated by the suppliers and providers of workspace – property professionals, facilities managers, architects and designers – rather than the ultimate users (a term, incidentally, that has different connotations in different contexts) of those spaces. The lack of a user voice in the decision-making process means that the views and needs of actual users often become replaced by those of ‘imagined users’iv.

To put it another way, it is often easier to make assumptions about users’ needs, behaviours, and attitudes, than actually to go to the effort of finding out about them. However, the ‘easier’ approach is also usually far more dangerous.

The lack of a user voice in workplace projects is also symptomatic of the way decisions tend to be made in projects and organisations more generally. It is common for decisions in workplace projects to be decided by a small group of ‘experts’ (including senior leaders who may certainly command authority but do not necessarily have workplace expertise) and then announced to the broader community of stakeholders.

The group are then left defending their decisions from criticism by stakeholders. This ‘decide, announce, defend’ (DAD) approachv often leaves people feeling ‘done to’ and therefore dissatisfied. In this way, the process of changing a workplace can have a significant and negative bearing on how people perceive the workplace product….

Please login to read the full article

Unlock over 1000 articles, book reviews and more…